Mental and Physical

What goes on behind the scenes when an athlete is injured?

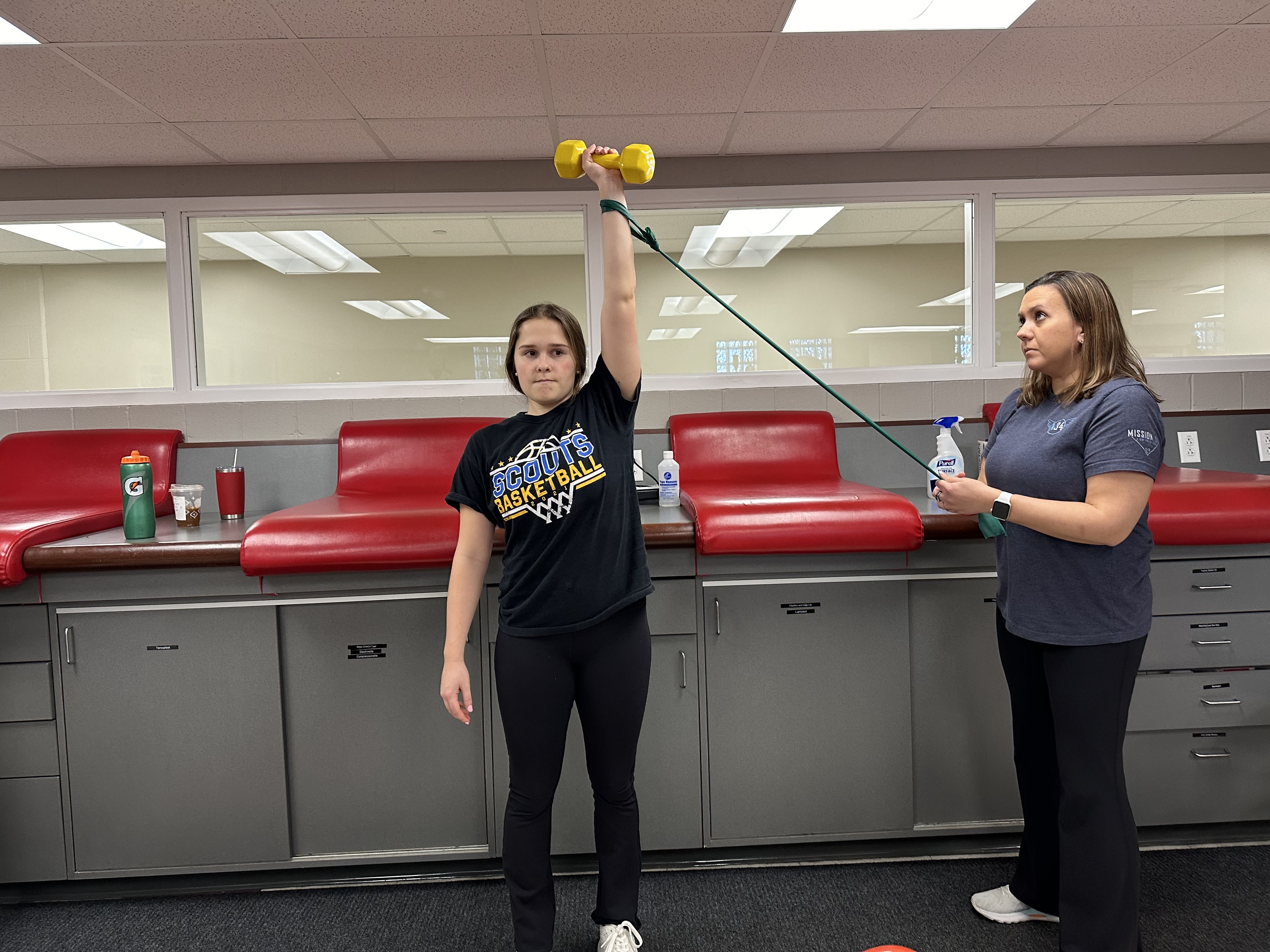

Trish stands a couple feet to the side of her athlete, Margaret, holding one end of a green band. The other end of the band is looped around Margaret’s wrist. This creates tension as Margaret presses a 9 pound yellow dumb bell above her head. A simple exercise becomes challenging to execute.

Margaret bites her lip as she resists the pull of the band. She is determined not to let her arm be pushed off course.

“Have you ever put a hoodie on backwards?” Trish asks, all business.

Margaret’s concentrated face falls apart into a smile and giggles. She drops the weight to her side. Trish laughs with her, and then her lips break into a smile too.

“You do it a lot?” Margaret asks with a laugh.

“Not a lot, but I just think it's funny when it happens.”

When Margaret begins the next set of repetitions of the exercise, both their faces are still bright.

*Name of athlete has been changed for privacy purposes.*

Trish Harris knew by the time she was in eighth grade that she wanted to go into medicine. At the time, she was leaning towards Physical Therapy. She had no idea what Athletic Training was. That all changed when she was in ninth grade.

“I was watching an Ohio State football game, and I saw these people going out to help an injured football player,” Trish said.

She thought what they were doing was so cool, so she looked it up and what it might entail. In her search, she learned that they were athletic trainers. After that, she worked towards becoming one herself.

Trish has been in the profession for twenty years now. She began working with Denison University sports medicine in the fall of 2008. In 2016, she became the Head Athletic Trainer.

“I stopped counting when I relived the 13th year, like six times in a row. I thought my 13th year was the year that we lost Sean. I thought my 13th year was the year we had COVID. I thought my 13th year was COVID year, when we were in masks the whole year and testing,” she said.

“I didn't like that that was something shameful.”

She has become the champion of mental health advocacy for athletes at Denison. It is not something she was always passionate about, but getting help for mental health was something that was normalized in her household growing up.

With a mom who went to counseling regularly to cope with aging parents, and a dad who was a war veteran, she has never viewed going to therapy in a negative way. She herself had been going on and off, until 2012 when a couple of negative comments from athletes on a survey got to her.

“In that particular year, the negativity piece really hit me hard, and made me kind of realize, like I needed to maybe go back to my counselor or seek out a new one. Because I saw some qualities in myself I didn't like and I wanted to change. So, I started going back,” she said.

Unfortunately, not everyone was as open and willing to talk about mental health as she was.

“I had a supervisor at the time who told me not to talk to anybody about the fact that you go to counseling, like keep that amongst us and amongst yourself. I didn't like that that was something shameful. But then I was pretty quiet about it for the next six years.”

"You need to feel all these emotions because it's the only way you're gonna get through them."

Wynne Hague was supposed to be the starting goalie for the Big Red's Women's Soccer team this year. All that was ripped away in an instant when she tore the Anterior Cruciate Ligament, ACL, in her knee at practice one day.

What does it feel like to watch an entire season from the sidelines?

Photo courtesy of Julie Lucas.

Photo courtesy of Julie Lucas.

Photo courtesy of Julie Lucas.

Photo courtesy of Julie Lucas.

Trish had been seeing Sean Bonner a couple times a week following a labral repair in his right shoulder in the fall of 2018. Sean was a pitcher on Denison’s Baseball team. Having the surgery meant that he was not going to be able to pitch the coming season in the spring. He was sidelined.

She was with the field hockey team when she received a call from the school asking if she had seen Sean recently. The field hockey team had won the North Coast Athletic Conference tournament, and received the automatic qualifying bid into the Division III National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament first round at Lynchburg in Virginia.

“I was like, I'm in Virginia, his mom's here too, to see a girl he had grown up with play,” she said.

Sean was missing.

“They said ‘you can't say anything to her until the university calls.’ I said, ‘if they don't call her before the game's over, and she realizes I'm here, she's gonna ask me how he's doing. And I don't know how to respond,’” she said, recalling the chaos of that day.

It wasn’t until she was in the car, in the middle of nowhere Virginia, on the way back to campus with Brandon Morgan, former Denison sports photographer, that she got a phone call from her husband. Then they received the news that no one ever wants to hear.

Sean was dead.

“When you're quiet about it, it just allows the stigma to fester.”

What her supervisor said all those years ago came back to her.

“After the fact, I'm thinking back to when I was told, don't tell anybody about your mental health journey, like keep that amongst yourself. So, after Sean died, I don't shut up about it,” Trish said. “I don't know that me being vocal about it would have changed anything. But wouldn't it be nice to know, like, if it would have had any impact?”

In the days and weeks following his suicide, Trish made the most of the opportunity she had to talk with his friends on the men’s basketball team. They were struggling.

“Their season started exactly one week later. And it happened to be the day of his funeral at home. So, they didn't get to attend it. And so they just kind of went straight into their season and never really had time to process their grief,” she said.

The men’s basketball coach kept telling his players to go to counseling, to get the help they needed. It was then, talking to these players, that Trish learned how little people knew about what counseling actually was.

“I had a basketball player say ‘I don't want somebody to tell me I'm crazy,’” she said. “I was like, ‘that's not how it works.’”

In hindsight, all the signs were there, but they aren’t always as obvious as we might think. She doesn’t call them red flags anymore, just flags. Sometimes they’re not red in your face, sometimes they can be orange or yellow. Sometimes they might be invisible.

“It's unfortunate, because then all of a sudden, you're like, okay, I start to see some patterns,” she said.

He, like most people whenever they experienced a season ending injury, seemed down. But when he was with Trish, she didn't really notice as much. It was the other things that were being said around him in her presence that set off alarm bells. She wishes she would have spoken up about it.

“I want them to know that they have somebody that’s always in their corner.”

Now, in addition to treating her athletes' physical injuries and ailments, Trish has made it her mission to look after their mental wellbeing.

Fun little toys and knick knacks are scattered throughout the training room and her office. Above one of the red treatment tables, a plushie Groot, that she crocheted herself, waits to be squeezed by an athlete for comfort. Several other crocheted plushies dot the room. All to help make this space one that feels safe and comfortable for everyone who visits.

During treatment, she’ll sometimes crack jokes to break the tension, or she’ll be super calm and caring. She just wants them to know that there’s one person who cares about them, regardless of what their playing time is.

Trish and the other trainers don’t want athletes to have to spend a lot of time in the training room instead of in action, but if an athlete has to be then they want them to have fun in here. They want athletes to know that they care, especially in cases when they are dealing with something long term, like an injury that requires surgery.

“I’ve gotten in trouble sometimes for being a mom. They’re like, ‘you’re not their Denison mom,’” she said. “But sometimes they just need somebody that’s nurturing.”

"I'm more than just a football player"

Nelson Austria underwent surgery twice to repair the labrum's in his left hip and right shoulder. After the second surgery, he found himself questioning his desire to continue to play football. The emotional, mental, and physical toll the two rehabilitation processes took on him was immense.

This audio story chronicles his journey, and how he came to an important decision. These surgeries allowed for Austria to open the door to his future beyond football.

“Does your child know that there's more to them in your eyes than just their athletic ability?”

“You guys [athletes] are onions. I don't think people see the full picture because we have put athletes on a pedestal and deemed that because they're successful, and because they exercise for a living they can't possibly have mental health issues,” she said.

She recognizes the weights that bear down on athletes. They are expected to be good students, to attend classes, to attend practices, and to compete and practice at a high level all the time. On top of that, there is the internal pressure they put on themselves to succeed, the pressure from coaches, and in some cases the added pressure of the expectations of family.

Every year, Trish has found that at least one athlete comes into the training room to tell her that they don’t want to play their sport anymore. But they don’t know how to tell their parents.

“I know that there's more to your child than just their athletics. Does your child know that there's more to them in your eyes than just their athletic ability?” Trish said.

After Sean’s death, she started working closely with the counseling center. Last academic year, she helped push for an athlete support group. This group, called From the Sidelines, was meant to help injured athletes, recently retired athletes, and anyone else learn to cope with life beyond their sport.

The group did not last long, but Trish hopes the counseling center will bring it back this year at some point.

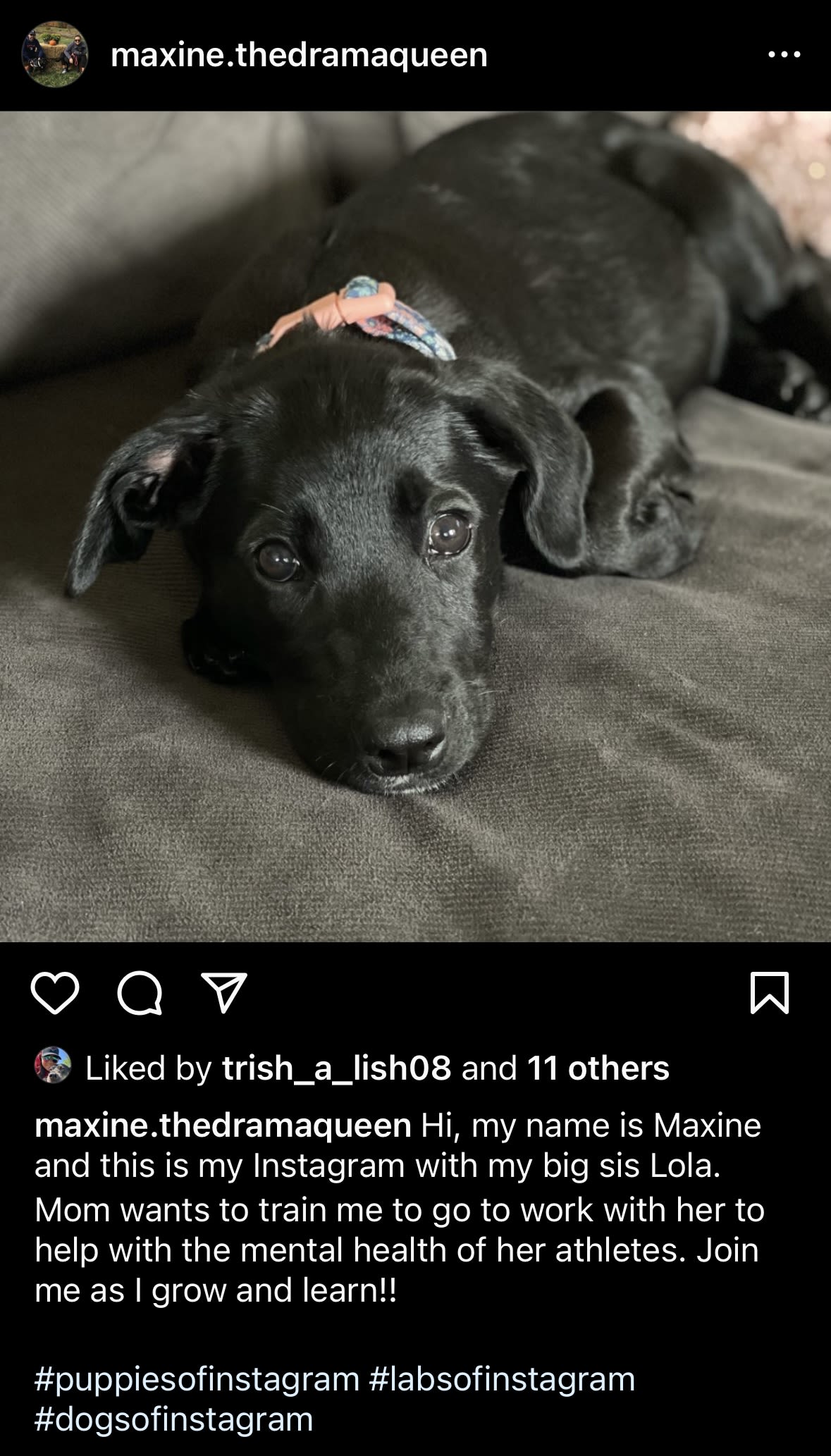

In addition to the support group, she is working on getting her dog, Maxine, certified to become a therapy dog. She wants to be able to bring Max in to work to help with her athletes.

“That's been the goal, like whenever we [she and her husband] talked about getting a second dog was to have that dog train to be a therapy dog,” she said.

Her plan is to be able to have hours that Max is in for people who want to see or do rehabilitation with her. At the same time, she wants to be careful to respect the people who are afraid of, allergic to, or just don’t like dogs. Trish recognizes that not everyone is a dog person, and she doesn't want her dog to end up being the reason why an athlete avoids the training room.

The training room is for everyone.

*Name of athlete has been changed for privacy purposes.*

An athlete, Rosa, lays on her stomach on one of the red treatment tables. She braces herself with her elbows, encasing a corn squishmallow inside. Her long dark hair falls in a curtain around her face. Her left foot is propped up on a wedge. Trish is dry needling her today.

“Are you ready?” She asks.

“Just do it!” Rosa says.

Trish makes quick work with the first needle, it's why athletes call her the Needle Ninja. She positions the small needle above the part of the hamstring she will be inserting it into, then gently inserts the needle into the muscle. At the same time, one of her fingers scratches Rosa’s leg. The sensation of the scratching distracts from the pinch of the needle.

“Ah!... Ahhhhhhhh,” Rosa says as the needle goes in.

Trish stops immediately. Waits for Rosa to calm down. Then proceeds to do the same thing three more times in different locations of her hamstring.

Athletes walk through the training room door everyday, each an individual, and Trish and the other trainers are there, for them.

“Because if I can prevent even one person from going down that road, then I will have honored Sean’s memory.”