Active Art

A conversation with community organizer,

musician, and painter, Allen Schwartz

Allen Schwartz graduated from Denison in 1970 with a BA in English. This is also where he practiced his activism. He went on to take part in movements against the Vietnam War, in support of labor and civil rights, in favor of environmental protection, and more. Allen ran the inmate law library at the Illinois State Penitentiary, and he taught in the adult education program for the Chicago Public Schools. More recently, he helped develop the Newark Think Tank on Poverty. The emphasis of this work has been to empower those facing the issues of endemic poverty to advocate for themselves.

In addition to his work as an activist, Schwartz is a musician and an artist. In the following conversation, Joshua Gingras focuses on Schwartz's artwork, looking at four pieces in particular, and talking through how each piece is a statement about community and fairness.

Denison Jam Session

Denison Jam Session

Joshua Gingras

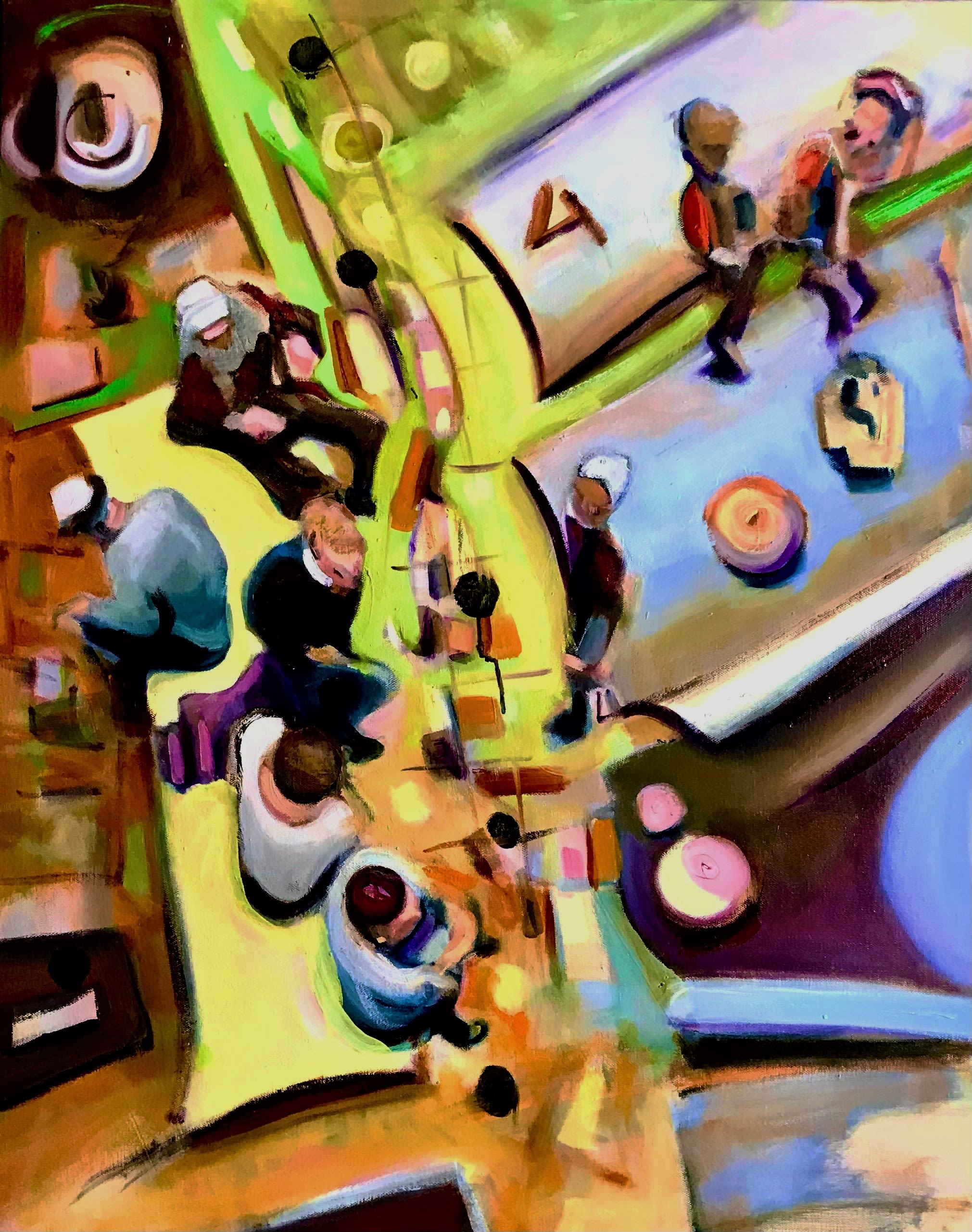

For this interview, I've asked you to select four works for us to discuss. The first is called Denison Jam Session. It looks like you're in this one (second from the right, in the orange cap).

Allen Schwartz

I am. It's the only picture I've ever put myself in.

Joshua

Why is that?

Allen

I guess it’s because I am really in it. I belong in that group.

That is a group of musicians that used to play in the student union at Denison every Wednesday. The point of this jam session is to make a place for everyone. Not all jam sessions are like that. But this one was a nice combination of extremely competent musicians—like that banjo player in the foreground, world-class, been to Nashville, the whole nine yards—and then folks who are just sort of from the community, like me, and the bass player, and the young girl who's playing the fiddle.

It's a fellowship, because people are working to make you feel you belong there. In some ways, that's the kind of seminal element of the world we'd all like to create, where people belong in creative activities—all ages, all kinds of people, there's always a chair for you.

Joshua

That also ties into the political work you do, community organizing.

Allen

So one of the main rules of a jam session is that when it is your turn, you choose a song that you want to lead on, and everyone else falls in behind you to try to make you sound better. It's a very democratic art form. The music is very predictable. Even if you don’t know the song you can figure it out.

When it’s your turn, the first thing you do is holler out the key, maybe the title of the song too, but most importantly for everyone joining in, the key. There are all kinds of inside jokes that bring us together too. For example, if somebody says the key of “A,” everybody, every week, every year, will say, Oh, it's the Canadian key, eh?

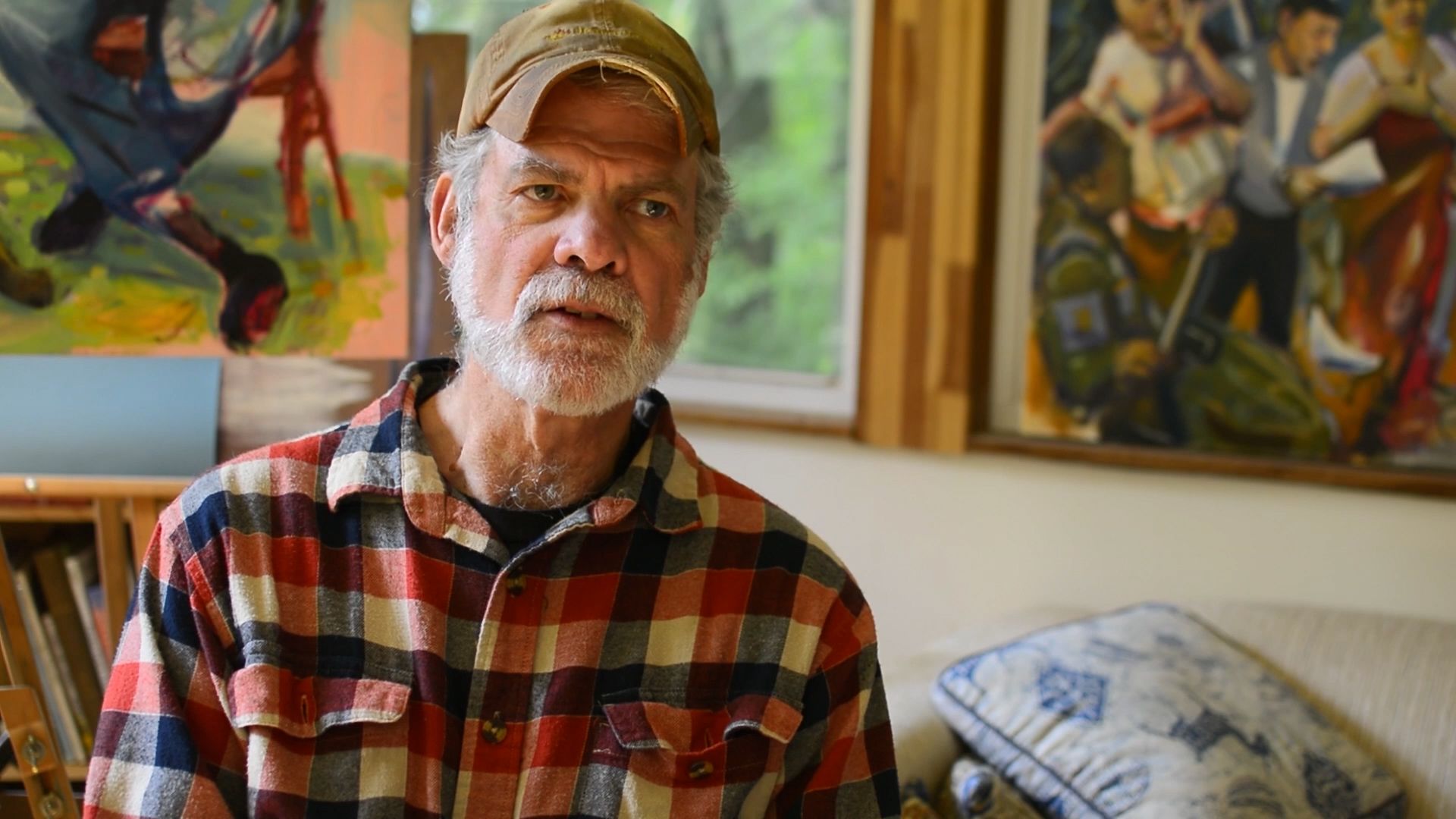

Allen Schwartz in his studio in Newark, Ohio.

Allen Schwartz in his studio in Newark, Ohio.

The Emporer's New Clothes

The Emporer's New Clothes

Joshua

Let's talk about The Emperor's New Clothes. I'll share what I shared with you [before this interview], about being young, being of a generation that went through a terrorist attack and economic crash, the NSA scandal, all that chaos. I was 10 years old when 9/11 happened, and then 17 when the economic crash happened. In fact, the last time gas prices were up to $4 a gallon was the same year in which I got my driver's license.

Allen

Ah, lucky you.

Joshua

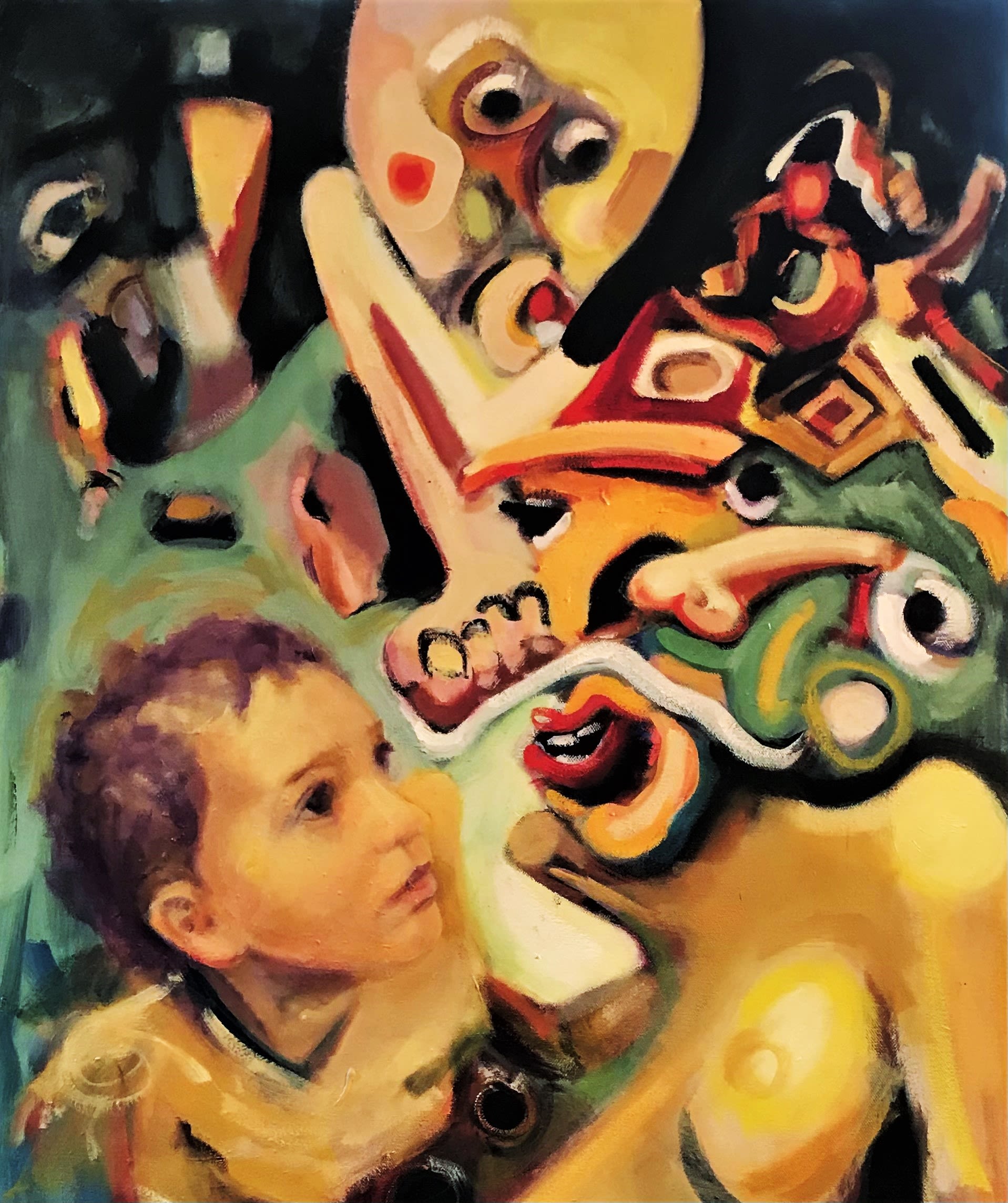

But this here, your painting, this young person looking at this creature of chaos, I mean, that "thing" on the right could stand for anything. So many different types of politics, so many crises. It's kind of gory in a way. There's this theme of body horror sometimes in your work, where figures distort, parts of people look gruesome. So when I look at this painting, that young person is me, looking at alternative news sources in 2001, seeing gory pictures of war and terrorist attacks.

Allen

So, given that response, I’d say it's a successful painting. When I painted it, I had something similar but slightly more particular in mind. The story of "The Emperor's New Clothes" is the most important archetypal story for modern times, I'd say. The centuries old story is about an emperor who lies to the people, claiming to have extravagant new clothes when he is, in fact, naked. The public is entranced and silent until one little boy speaks the truth about it. I used to ask people, when did you discover that the government lies to you? I think mine was the U2 incident [in 1960], where Eisenhower said, No, we don't have any pilots flying over Russia. And the next day Russia produced the pilot.

Actually, instead of the young boy, I had originally planned to put AOC (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) in there, because she is a truth teller, in her role right now, standing up to the Emperor, saying, What you're giving us is a lie. But I didn't like it as much, so I decided, I really want this ultimately to go on my grandson's wall, and for him to feel a part of that fairy tale. I don't want him to feel like the Emperor, I want him to feel like the kid who tells the truth. [It’s] what I would like my grandson to do when he grows up, and what I've sort of tried to do with my whole life as an artist. It’s also what you do as a writer. Be that voice, that truth teller voice, that is not afraid to say the Emperor's naked.

I've shown this to a number of people who say, “I liked it. I think the picture of your grandson is great, but what the hell is that on the right hand side?” I don't know what emperors look like, so I painted one that was two-faced. There's a green face and an orange face sharing the same head as a metaphor for "liar." I wanted it to be kind of ornate and chaotic, as I imagined the furnishings around an emperor would be, so I made the right-hand side of it abstract, less accessible.

The World's Five Great Religions as Seen by a Drone

The World's Five Great Religions as Seen by a Drone

Joshua

Let's transition into your third painting, The World's Five Great Religions As Seen By A Drone.

Allen

Yeah, the title is ... you know, from any above-the-ground perspective, there's not a lot of difference between the major religions of the world. So, one way to get that perspective is from the drone program, a program which I think is really problematic. From however high the satellites are, they pick out targets. So I took that perspective and tried to create figures which represented the different religions.

Joshua

It's a thematically dark painting, but you chose bright colors.

Allen

I think in bright colors. So, no matter what the theme is, I usually think artistically in bright colors, just the way I am. I've tried to do a couple of pandemic paintings, which turned out in dark colors. I did one about addiction, which was dark colors with bright colors on top. But usually, when I'm trying to tell a story, I think about bright colors.

I want it to kind of explode in the viewer's eye. In the painter world, we call it “popping”: You put two colors next to each other—a dark Catholic priest's vestment against a light yellow seat—in order to get it to pop.

And we have such a weird combination of dark and light in our world right now, right? Take a look at CNN, there are fashion shows and all kinds of stuff going on, while Ukraine is being razed. A shot of a drone strike becomes an everyday activity. All of a sudden, you've got a 30-foot crater where human life used to be.

I think there is some rationale for doing dark subjects brightly. I think cartoon and advertising culture, which I was brought up in, which everybody in this country is brought up in, uses bright colors. I think that's in our heads, as part of our culture, as opposed to 18th century or 17th century paintings, with all the darkly-nuanced backgrounds.

Empty Hands and the Edge of an Empty Table

Empty Hands and the Edge of an Empty Table

Joshua

Your fourth piece is called Empty Hands and the Edge of an Empty Table. It's harder for me to grasp.

Allen

As you know, we've been working with the issue of poverty, right? And it's not the poverty you might find in a Sudanese refugee camp, it's a poverty in the midst of plenty. You know the people we know are only a stone's throw from everything they need, except that it has to be bought.

Last week, I went to the house of a friend who was about to be homeless. He'd been working on that household for five years, but in 10 minutes, he was going to be out on the street. All he really had was his bike, a sidecar, a dog for the sidecar, a sleeping bag, a tent, and a gas stove. That was it. But his house was full of all the stuff that he had been using to put together a household for a human being. It's still the empty table, surrounded by stuff, and the empty hands that are extended all out to the edge of the empty table. There's no table left.

This friend of mine was leaving his table. He was going out on the street, no furniture, nothing. So, this is about poverty, the poverty we see here, people with nothing, but surrounded by a world of plenty. I know it's less accessible to people who view it, because I did it in an abstract format.

If you look at Van Gogh paintings, when he was still painting the Dutch, The Potato Eaters for example, the sentiment there is of great suffering. And that's not really the sentiment I was going for here. I'm going for the irony, the contradiction that we have with people in dire need of everything, at the end of their rope, at the end of the table, surrounded by the stuff they need, living in the dirt underneath some bushes here in Newark with their bicycle and their dog.

Joshua Gingras is a local writer. He can be reached at gingras.4@buckeyemail.osu.edu.

RETURN TO THE REPORTING PROJECT