Ancient brilliance

An open house at the Newark Earthworks celebrates UNESCO World Heritage designation

[Note: This multimedia story is best experienced on a desktop or laptop computer.]

The Newark Earthworks, and six other connected sites in Ohio, were recently added to the UNESCO World Heritage list, the first such listing in Ohio. On Sunday, October 15, a commemoration was held in Newark to mark that occasion.

A formal ceremony was held at the Great Circle on Hebron Road. Both Jeff Hall, the mayor of Newark, and Mark Johns, the mayor of Heath, spoke at the event, since The Great Circle is so large a structure it touches both cities.

One mile away, off 30th street, the Octagon Earthworks was also open for public access. This is currently the site of the Moundbuilders Country Club golf course. Four times a year the golf course shuts down to allow public access to the earthworks at that site. On all days, a small path, and an observatory platform, are open to the public.

The Reporting Project joined Brad Lepper, archeologist for the Ohio History Connection and visiting assistant professor at Denison Univerity, as he led a large tour of the Octagon Earthworks. Following are excerpts from his tour, photographs from the day, and graphics to illustrate his talking points.

Author's notes: Some edits have been made in the transcript for clarity and conciseness.

Jeff Hall (at the podium, our right), mayor of Newark, Ohio, and Mark Johns (left), mayor of Heath, address a crowd at the Newark Earthworks Commemoration Ceremony.

Jeff Hall (at the podium, our right), mayor of Newark, Ohio, and Mark Johns (left), mayor of Heath, address a crowd at the Newark Earthworks Commemoration Ceremony.

The museum at the Great Circle was open for the special event. Its normal operating hours are Thursday through Saturday, 10 a.m. through 4 p.m.

The museum at the Great Circle was open for the special event. Its normal operating hours are Thursday through Saturday, 10 a.m. through 4 p.m.

The Octagon Earthworks tour begins at this sign. Brad Lepper is pointing toward the highlighted octagon, The Great Circle is below his wrist. The structures above Lepper's arm appear as documented by the earliest European settlers. These structures have since been destroyed by the development of Newark.

Brad Lepper: So [these earthworks were] built by the ancient Indigenous people that archeologists refer to as the Hopewell culture. They lived in this area between about AD one and 400, and contrary to what this might look like, it was not a city these people lived in.

Tiny little communities were scattered all over these valleys. They were so small, archeologists don't even call them villages. We tend to call them hamlets, but you can think of them more as homesteads where a couple of families are living together, hunting, fishing, gathering, but also gardening. Probably not the plants you are thinking of because they didn't have corn yet.

Corn was domesticated in Mexico. It made its way up into the Ohio Valley about AD 900. So these people were cultivating what's called the Eastern agricultural complex. Sunflowers and squash would be the plants we're most familiar with, but also plants with small seeds, like May grass, little knotweed, goosefoot. These were actually domesticated plants.

This was pretty cool. The Ohio and Mississippi Valley was one of only about eight places in the world where plants were domesticated by Indigenous people, not just collected and gathered.

Brad Lepper begins his tour of the Octogon Earthworks. One wall of the octagon is present just behind the group.

Brad Lepper: So these people, these ancient Indigenous American Indians, built these earthworks with very simple technology. And by simple, I mean it's as simple as you can imagine. Pointed sticks, clamshell hoes, and baskets.

So they would dig the earth up, fill up a basket, and carry it one after another to build this incredible geometry. One conservative estimate, based on this map, is that they used seven million cubic feet of earth to construct the Newark Earthworks. The scale is enormous.

And since we're now a World Heritage site, I think this might be my first tour of the Octagon Earthworks as a World Heritage site. That's neat.

Author's note: Click play below to hear Brad Lepper's voice as he talks about the Earthworks.

"My first tour of the Octagon Earthworks as a World Heritage site," said Lepper. He gets a round of applause.

Brad Lepper: I think people came from the literal ends of their world to participate in religious ceremonies here. We have very little evidence of what was in the burial mounds at Newark because the focus of mortuary activity was destroyed early on in the history of Newark. The Ohio canal went through it. The Central Ohio Railroad went through it, and it became an area of industry. All those mounds were obliterated.

But in Chillicothe, at Seip Mound, and at the Hopewell Mound Group, artifacts were found in those mounds made from shells from the Gulf of Mexico, copper from the Upper Great Lakes, mica from the Carolinas, and even obsidian, a black volcanic glass. Of course, there are no volcanoes in Ohio, so it had to come from somewhere else. Turns out, every form of obsidian has its own chemical fingerprint that's unique. And the obsidian that was excavated from Hopewell Mounds mostly came from Yellowstone Park obsidian cliffs there.

So that's what I mean by offerings were being brought here from the ends of their world, eventually deposited in these mounds as ceremonial offerings.

Map identifying the exotic materials found in Hopewell Ohio, and their distant sources throughout North American. Courtesy Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Map identifying the exotic materials found in Hopewell Ohio, and their distant sources throughout North American. Courtesy Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Brad Lepper: This whole site is built on a high glacial terrace. There's never been flooding here since the end of the last ice age. And the whole earthwork site is surrounded by water. It's got Raccoon Creek to the north. The south fork of the Licking River to the east, and down here to the south is Ramp Creek. And the tributaries of Ramp Creek and Raccoon Creek nearly come together here in the west.

The ceremonial activities at The Earthworks were surrounded by water, in the same way that the middle world, the earth, was believed to be surrounded by the waters of the underworld. So The Earthworks represented and reproduced the cosmology of Indiginous Americans.

Aerial view of the Octagon Earthworks. Currently, the Moundbuilders Golf Course sits atop the site. However, the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that the Country Club must move. The final phase of procedings is underway. Picture courtesy of Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Aerial view of the Octagon Earthworks. Currently, the Moundbuilders Golf Course sits atop the site. However, the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that the Country Club must move. The final phase of procedings is underway. Picture courtesy of Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Teresa Stanonick is one of many on the tour who asked questions about the Earthworks and the people who built them.

Brad Lepper: The main axis of this site is lined up to the northernmost rise of the moon, which happens once every 18.6 years. There are actually 8 alighnments. The northernmost rise, the southernmost rise, the northern minimum rise, and the southern minimum rise. And four corresponding set points and alignments.

Author's note: October, 2005, was the last time the moon rose at its northernmost point. A public event was scheduled at the Octagon Earthworks, but it was cancelled by the Moundbuilders Golf Course because there had been rain earlier in the day. A small group did observe that moonrise, and Brad Lepper was among them.

Brad Lepper: Being able to stand here and see the moon rise there, having no knowledge of the details of their religion, I felt a spiritual experience seeing that moon rise, standing where the people that I've been studying for my whole career stood and watched the same moon rise in the same place. It was amazing.

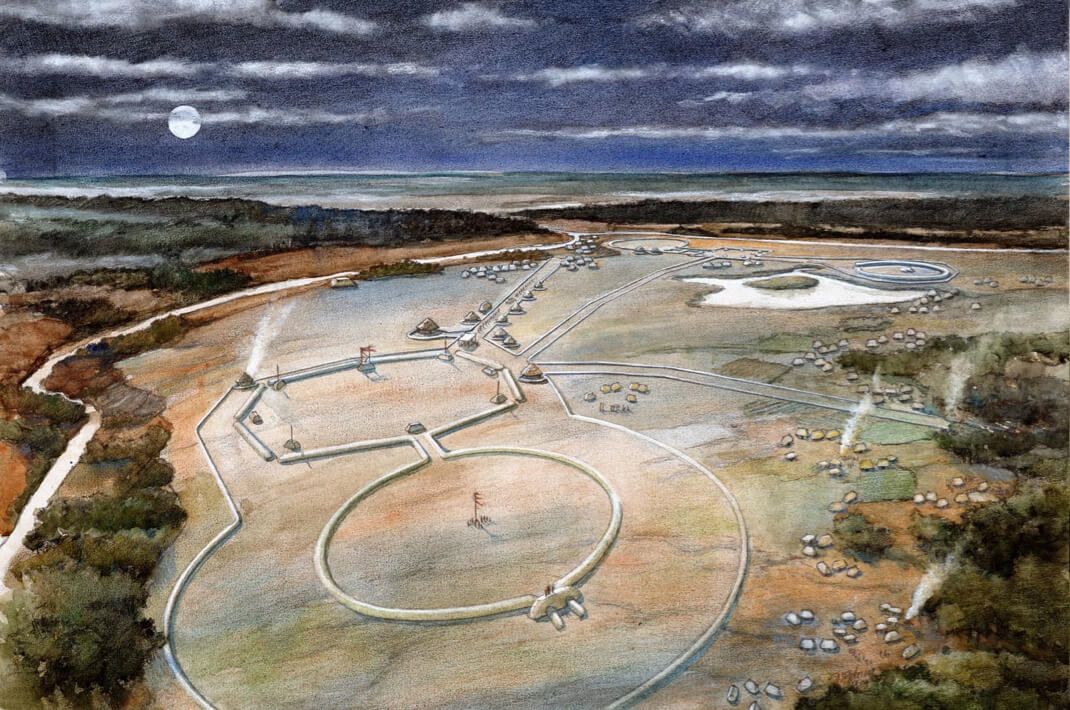

Artist's rendering of the Octogon Earthworks. The main axis of this site is lined up to the northernmost rise of the moon, which happens once every 18.6 years. Brad Lepper was present at the site during the most recent event. Image courtesy Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Artist's rendering of the Octogon Earthworks. The main axis of this site is lined up to the northernmost rise of the moon, which happens once every 18.6 years. Brad Lepper was present at the site during the most recent event. Image courtesy Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

Brad Lepper: Written language is supposedly one of the characteristics of civilizations. People lived in cities, they had hierarchical leaders.

The Hopewell had monumental architecture on a scale that any of these civilizations at that time were building. But they didn't have any of the other things. They didn't have written language, that we know of. They didn't live in cities. They didn't have a hierarchy of leaders with an authoritarian leader at the top.

So it's one of the mysteries, and I think it's a mystery that it behooves us to ponder because these people, thousands of people, came here voluntarily, cooperating to build these things, and they didn't have somebody telling them to do it. They lived in scattered little communities that if they didn't want to do it, they could just move on and go to some other valley and not be ever heard from again.

So the idea that hundreds or thousands of people could work together to achieve something of amazing grandeur, that is something that we should be thinking about.

Brad Lepper, lead archeologist for the Ohio History Connection, believes we should ponder the mystery of the civilization that built these earthworks. In the background, the vast expanse within the Octagon Earthworks. Photo by Doug Swift.

Brad Lepper, lead archeologist for the Ohio History Connection, believes we should ponder the mystery of the civilization that built these earthworks. In the background, the vast expanse within the Octagon Earthworks. Photo by Doug Swift.