Recycling or Polluting?

Is chemical recycling a solution to plastic waste or just a dangerous detour

By Emma Amlin & Audrey Brink

A Moment of Panic

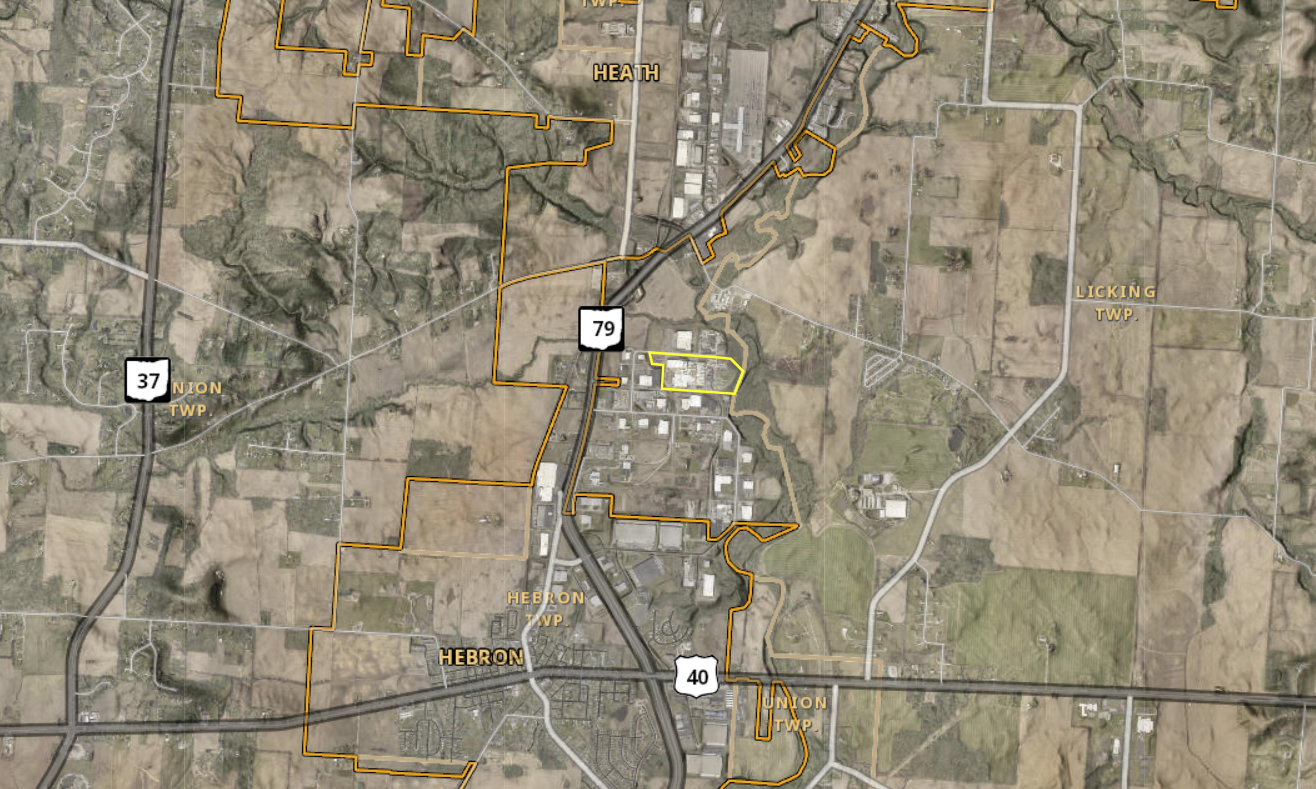

It was a blue sky day in February when Amanda Rowoldt decided to make the 50-minute drive from Dublin, Ohio to Freepoint Eco-Systems in Hebron, Ohio.

She'd been reading a lot about the environmental problems with chemical recycling, but she wanted to see the plant that had located in Licking County for herself.

She pulled up next to the 500,000 square-foot-building.

She saw dark smoke flowing out from two smokestacks in the middle of the building.

“I felt nauseous, I felt dizzy, and I had a headache,” she said. She pulled out her phone to record a video.

Rowoldt is a mom, cancer survivor and activist.

As she drove out of the industrial park, she passed a neighborhood. She couldn’t help but notice toys in the yards of houses she passed.

“I knew I wanted to capture the footage because it was so important, but at the same time, it was very triggering.”

Rowoldt has two sons, ages 7 and 10. She works with the environmental group Moms Clean Air Force. She joined the group after realizing that the way to end plastic waste was to work together. “I realized, I’m putting too much of a burden on myself. This is a group effort.”

Rowoldt then shared the video of the pollution on the Moms Clean Air Force, where it reached a wider audience, including the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA).

Amanda Rowoldt, member of Moms Clean Air Force. Photo provided by Amanda Rowoldt.

Amanda Rowoldt, member of Moms Clean Air Force. Photo provided by Amanda Rowoldt.

Annabel Edwards, associate professor in chemistry. Photo provided by Annabel Edwards.

Annabel Edwards, associate professor in chemistry. Photo provided by Annabel Edwards.

Understanding the Problem

Traditional recycling methods, called "mechanical recycling," shreds and pelletizes plastic so it can be reformed into new products. However, this method is limited. It only works with a few types of plastic, the plastic degrades and can only be reused a limited number of times, and Americans only recycle 7.5% of the plastic they use.

Advanced recycling, also known as chemical recycling, uses a process called pyrolysis. This process can accomodate all plastic, so the petroleum industry hails it as a solution to the world's plastic waste problem. It superheats the plastic in giant kilns, reducing it down to its original chemical elements. The resulting feedstock can be used to create new plastic products.

Environmentalists argue that pyrolysis, which involves heating plastic to extreme temperatures, is more like incineration than true recycling, and in some states it has that designation.

Dr. Annabel Edwards, chemistry professor at Denison University, thinks it gets at what the real meaning of the word "recycling" means.

“In my mind, [pyrolysis is] not necessarily recycling," Edwards said. "I think that is a word that is debated. I mean, there’s upcycling and downcycling. And to me, incineration is very much downcycling.

“Downcycling is when you are starting with something useful, but now it is no longer useful," she said. "It is a byproduct or waste. Upcycling is when you add value.”

ProPublica did an indepth study to determine how much of the plastic that enters the pyrolysis system comes out as reusable material. It came up with 15-20%.

Graph from the ProPublica report. By contrast, about 80-85% of input in mechanical recycling comes out as new product.

Graph from the ProPublica report. By contrast, about 80-85% of input in mechanical recycling comes out as new product.

The Reporting Project tentatively scheduled a meeting in March with Jeff McMahon, managing director of Freepoint Eco-Systems, though McMahon and all Freepoint representatives stopped responding to The Reporting Project, and did not respond to further requests for comment prior to publication.

Environmentalists like Victoria Abou-Ghalioum, of the Buckeye Environmental Network, are concerned that in the pyrolysis processes, toxic chemicals are separated out and released into the environment. “Dioxins and furans are highly toxic chemicals that result as byproducts of the manufacturing process,” Abou-Ghalioum said. “They occur at high heats, [and] are known to cause cancer."

“Downcycling is when you are starting with something useful, but now it is no longer useful, it is a byproduct or waste. Upcycling is when you add value.”

Limitations

Freepoint has stressed that it intends to operate within the limits of all regulatory governing agencies. The Reporting Project reported in February that Freepoint had received an NOV (notice of violation) from the Ohio EPA for indoor air pollution.

Dina Pierce, a public information officer from the Ohio EPA, said that “The agency is open to proven, new recycling processes that help grow Ohio’s circular economy and reduce waste streams, provided they comply with and adhere to state and federal rules to protect the environment and human health.”

OEPA has permitted Freepoint to emit 55.7 tons of VOCs (volatile organic compounds) per year, 25.8 tons per year of nitrogen oxide, 6.1 tons per year of carbon monoxide, among others. Pierce notes that for context, the average car emits 5 tons of carbon dioxide per year.

The National Resources Defense Council contends that the technology releases carcinogens like benzene and dioxins.

Pierce notes that just because this is what a company is permitted to emit, that doesn't mean it is what they do emit. Generally it is up to companies to self-moniter their emissions.

However, as a result of Rowoldt's video, OEPA took a reading of Freepoint's emissions and issued a NOV (notice of violation) on March 7, 2025. According to Pierce, Freepoint has not operated since.

Freepoint did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this issue.

Flowchart of Pyrolysis (Created by Emma Amlin & Audrey Brink)

Flowchart of Pyrolysis (Created by Emma Amlin & Audrey Brink)

Freepoint Eco-Systems, 522 Milliken Road, Hebron Industrial Park. Photo by Doug Swift.

Freepoint Eco-Systems, 522 Milliken Road, Hebron Industrial Park. Photo by Doug Swift.

Collaborating for Change

Dr. Edwards concludes that the real solution to plastic waste is to end plastic consumption.

Amanda Rowoldt agrees. “The glimmer of hope is that we can make different choices," she said. "To basically tell all these people and companies, we just don't want this, don't make it, don't produce it.”

Alfa Laval is a company in Richmond, Virginia that consults on pyrolysis. According to their website, they believe this technology is "a sustainable way of managing plastic waste to reduce its impact on our environment while also providing a profitable opportunity for businesses."

They also list a number of obstacles the technology faces. These include emissions challenges, economic challenges, especially regarding such high energy demands, and water management.

Freepoint continues its efforts to get its Hebron plant in production. In March 2025, Freepoint announced that the company had obtained a $50 million financing deal with German company ING.

Freepoint Managing Director Jeff McMahon told Recycling Today, “We are excited to be partnering with ING in demonstrating that plastic upcycling facilities that utilize new technology have access to the project finance loan markets.”

There was no mention in the story about how Freepoint intends to use that money, and the company has not responded to The Reporting Project to elaborate.

Amanda Rowoldt continues her activism related to the facility. She says that it is important that people are more educated about what happens to plastic after we are done using it because there is no real solution to plastic waste.

She said, “The message is really: How can we collectively come together to make the change that is so desperately needed?”