Tear Tactics

How corporations use green ads to hide their pollution

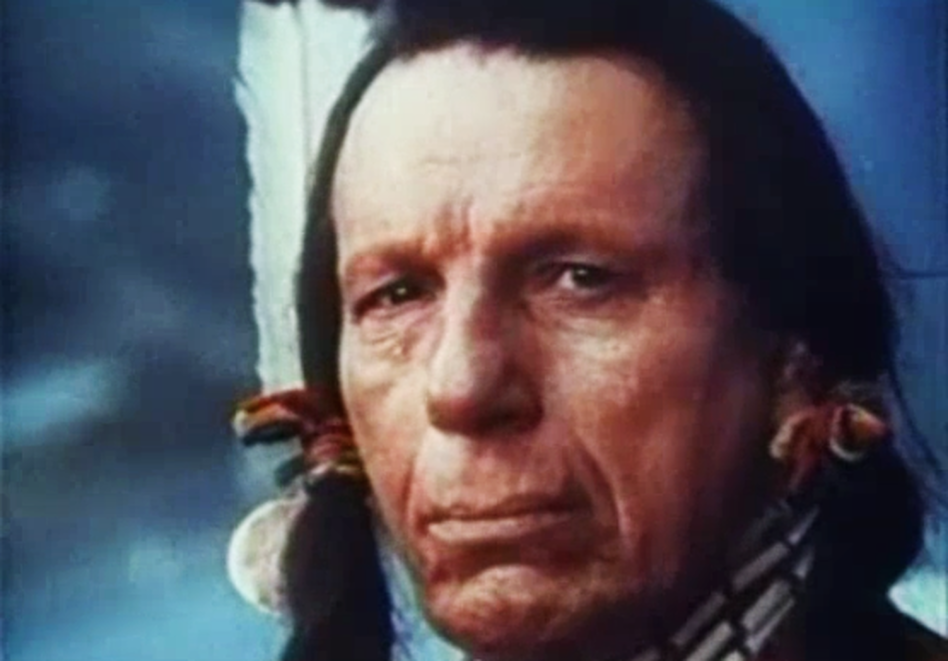

ANative American paddles his canoe through pristine water. Then, bits of litter clutter the water. Smoke pours from stacks across the shore. He pulls his canoe aground amidst scattered garbage, and walks toward a busy freeway.

A deep-voiced narrator intones, "Some people have a deep abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country."

A passerby tosses a bag out the car window, emptying his fast-food leftovers at the Indigenous person's feet. A single tear falls from his eye.

The voiceover continues: “And some people don’t.

“People start pollution. People can stop it.”

The commercial, first broadcast in 1971, turned heads nationwide. It earned two Clio awards for best public service announcement. The “Crying Indian” ad provoked an intense emotional reaction from viewers that still resonates today.

Lorraine Bowman, a Granville, Ohio resident, remembers the ad well. "It made everyone stop," she said. "I was just telling my husband we need another 'Crying Indian.'"

Keep America Beautiful (KAB), the organization behind the “Crying Indian” commercial, as well as many like it, was formed by leaders from the packaging industry, companies like PepsiCo and Coca-Cola. These are the very corporations who run the smoke-emitting factories, and produce the throw-away products.

“It made everyone stop. It completely changed the United States. I was just telling my husband we need another 'Crying Indian.'”

Lorraine Bowman, Granville frequent

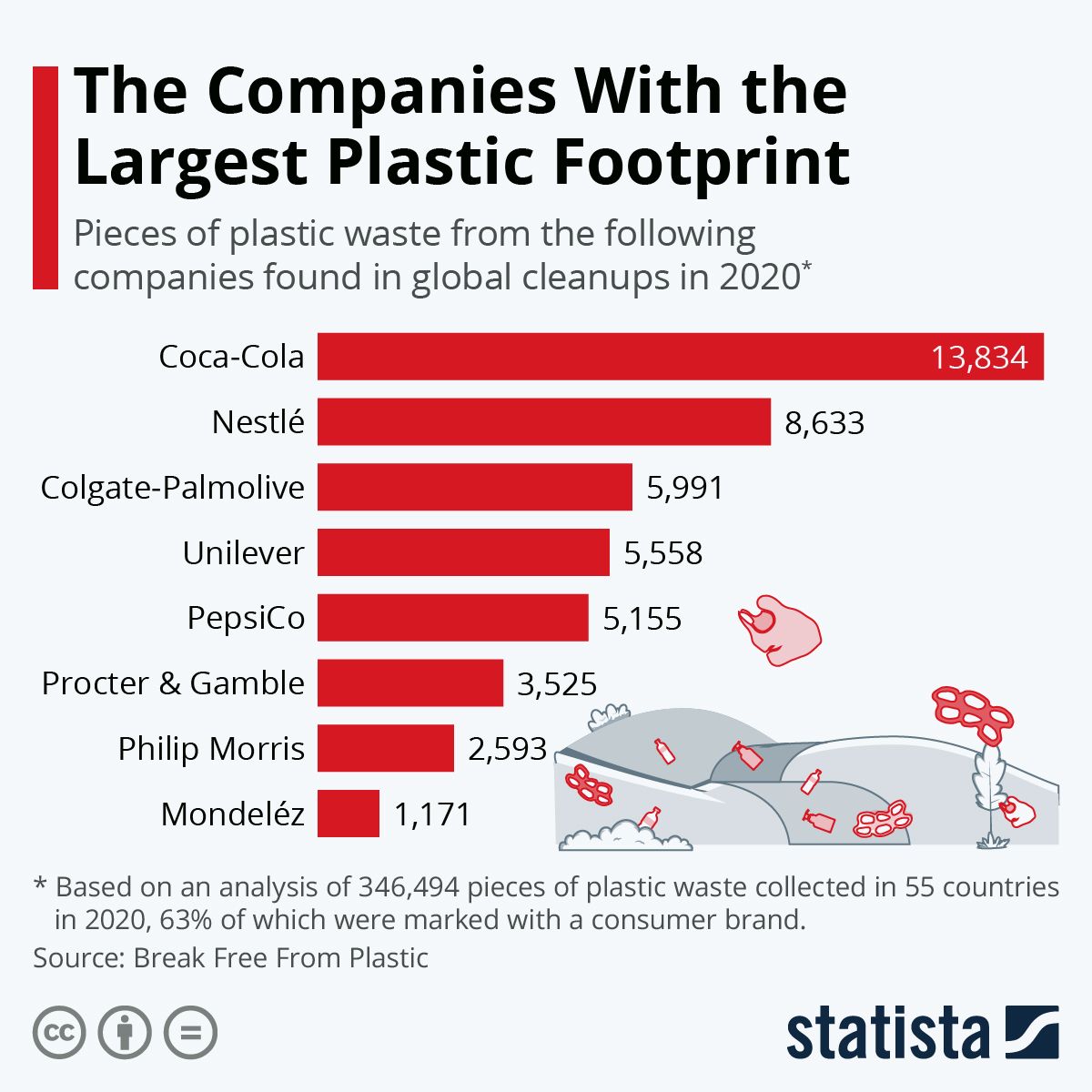

Break Free From Plastic’s 2020 brand audit (Photo by Statista)

Break Free From Plastic’s 2020 brand audit (Photo by Statista)

There was an agenda in the ad that almost everybody missed. Environmental advocates said the sponsors of the ad put the onus on "people" to clean up the mess, taking the blame away from the corporations making the garbage — allowing them to increase their production of it, and therefore their profits.

In a letter to KAB President Roger Powers in 1993, Rick Hind, former executive director of Greenpeace USA, stated that, “KAB continues to put the blame for waste generation and the responsibility for waste management on the public sector, when the real polluters are the industries that manufacture, sell, bury and burn the waste.”

In the last two decades alone, plastic production more than doubled, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). As the concern about the effects of plastic began to build, so too did the need for large corporations to protect their sales, according to Hind.

"Greenwashing" is a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986 to describe major corporations deliberately misleading consumers to capitalize on the ‘eco-friendly’ movement. Creating the illusion of eco-responsibility, organizations just like KAB deflect their own harmful actions.

"Greenwashing" is a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986 to describe major corporations deliberately misleading consumers to capitalize on the ‘eco-friendly’ movement.

While Keep America Beautiful is a popular example, companies have been using greenwashing as a marketing tactic for decades, often using the illusion of small, independent ‘grassroot’ organizations to sell their product.

“If [large corporations] can say it through somebody else, it seems independent, then there’s power,” said John Passacantando, former director of Greenpeace USA, in the documentary Merchants of Doubt. The documentary reveals how higher ups often spread misinformation as a means of protecting corporate interests.

Passacantando described corporations' hand-selecting representatives to lead seemingly-independent companies. “It becomes a whole new cast of characters,” Passacantado said. This "new cast of characters" seems to have the interests of consumers and communities in mind.

In 2020, the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) published an advertisement urging the public to recycle to stop the plastic crisis. The ad contains visuals of plastic bottles polluting oceans and mounds of trash covering once-green landscapes. A voiceover states, “We have the people that can change the world.”

Much like Keep America Beautiful, the AEPW is funded by representatives from ExxonMobil, Chevron Phillips Chemical and Shell, and many more in the petrochemical industry, according to their website.

“Déjà vu all over again,” Lew Freeman, a former leader in the Society of Plastics Industry (SPI) told NPR. Freeman worked closely with executives of the oil and plastics industry. “This is the same kind of thinking that ran in the '90s. I don't think this kind of advertising is helpful at all.”

An Unearthed story says that the AEPW creates 1,000 times more plastic than it cleans up.

The most recent efforts by the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) is "advanced recycling," sometimes called "chemical recycling." The theory is that plastic waste can be gathered, fed into superheated kilns, reduced back to their essential molecular compounds, and used to make more plastic.

The industry calls this the creation of a "circular economy." There are about 11 such advanced recycling plants in the United States. One, Freepoint Eco-Systems, is in the Hebron Industrial Park, in Licking County.

Freepoint Eco-Systems began ramping up production in fall 2024.

Upon opening their website, viewers are greeted with a green mountain vista, pictures of plastic waste and disturbing statistics about how bad the plastic waste problem is. There's a picture of a seagull with plastic stuck to its beak. We learn that “100+ billion single-use plastics are thrown away each year.”

There are bright airy photos that show a pristine environment, and give hope for the future. But scaling up advanced recycling is a challenging — and filthy — enterprise, and that Freepoint has received at least two notices of violation (NOV) from the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in 5 months.

Freepoint Ecosystems webpage, 2025.

Freepoint Ecosystems webpage, 2025.

Freepoint Ecosystems webpage, 2025.

Freepoint Ecosystems webpage, 2025.

“The plastics industry basically is not telling the truth," said Licking County Commissioner Tim Bubb. "Because it's in their best interest as a corporate entity to keep chugging it out, because it's a huge profit volume." From a corporate standpoint, Bubb noted, the plastics industry is obligated to keep producing plastic as a means of keeping their companies afloat.

Scientists and environmentalists argue that the real solution is for the corporations to stop producing so much plastic.

“That’s the whole dilemma of plastic," Bubb said. "We all want cheap plastic packaging. We never really saw it as the evil that it is, and it doesn’t go away easily, so we’re drowning in it.”